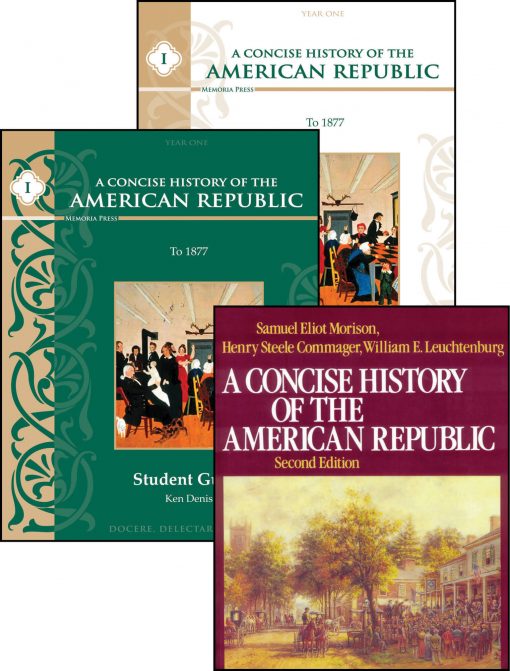

Memoria Press has created a two-year course for high school titled A Concise History of the American Republic. The course is built around an 880-page textbook, also titled A Concise History of the American Republic by Morison, Commager, and Leuchtenburg.

This second-edition textbook has a long history. The material for this book is drawn from The Growth of the American Republic, a book first published in 1930 and written by Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager. The Growth of the American Republic went through six editions up through 1969, with material added each time to cover the intervening years. William E. Leuchtenburg joined the other two authors to work on the sixth edition. Then Leuchtenburg, with some assistance from Morison and Commager, used the material from that sixth edition to create the shortened and revised book, A Concise History of the American Republic, which was first published in 1977. The textbook for this course, the second edition published in 1983, was updated by Leuchtenburg with some editorial input from Commager. It covers through the Reagan era. (Yes, this leaves you on your own to cover the intervening years up to the present.)

This textbook is used for two years. The first-year course covers the first 19 chapters of the textbook, and the second-year course covers the remaining chapters: 20 through 36. Each course has its own student guide and teacher guide, all written by Ken Dennis for Memoria Press. The student and teacher guides each have a one-page course schedule showing reading assignments and tests. The student guides' “Reading Notes” for each chapter are generally key points to remember. The Reading Notes are followed by five to fourteen questions that require answers varying from one sentence to a few paragraphs in length. The student guides have lines for students to write their answers directly in the books, although some answers might require more space than is provided. The teacher guides have the same content as the student guides but with suggested answers overprinted. The teacher guides also have three tests each and the answer keys for the tests. Each test has fill-in-the-blank questions and one essay question that will require a lengthy response.

Interestingly, the first course has students skip reading the first chapter. Instead, teachers are directed to give a lecture on the main explorers and adventurers in the New World. The first two chapters of the book are then grouped together for the first student assignment. There’s only one question regarding early explorers (about Christopher Columbus), and the rest of the questions are based on the second chapter. I don’t know the rationale of the course author for skipping the first chapter in the book, but that chapter does begin with some highly speculative information regarding the first settlers in the Americas. Most students will have learned about explorers and Native Americans in previous courses, so you might be able to skip both the chapter and the lecture.

Even though it’s supposed to be a concise history, the textbook presents far more detail than students usually learn in high school courses. But that makes it all the more interesting to read. The authors frequently write about personal characteristics of important historical figures and about the motivations or machinations behind events. For instance, we learn about the character of George Washington as the authors tell us,

He had the power of inspiring trust, but not the gift of popularity; fortitude rather than flexibility; the power to think things through, not quick perception; dignity, but none of that brisk assertiveness which has often given inferior men political influence….And beneath his cool surface there glowed a fire that under provocation would burst forth in immoderate laughter, astounding oaths, or Olympian anger ( p. 127).

The overall tone of the textbook is religiously and politically even-handed until, in the last two chapters, some political bias creeps into the coverage of the latter half of the twentieth century. Subtle negativity toward President Eisenhower is followed by laudatory treatment of President Kennedy. A generally positive attitude toward the subsequent Democratic Presidents Johnson and Carter contrasts even more sharply with the critical treatment of Presidents Nixon and Reagan. For instance, Reagan is described as a right-wing ideologue” ( p. 76), and further along, it says, “it was hard to connect so likeable a man to the mean-spirited programs with which he was often associated or so plausible a man to the implausible program he sponsored” (p. 763).

The political bias in the latter part of the book could profitably be used for discussion or further research to provide some balance. Even having students search the text to identify loaded language that might influence readers' opinions would be useful as an exercise in critical thinking.

The textbook covers so much information that the questions in the student guide are necessarily selective about what students are required to know. And questions on the tests don’t necessarily reflect the same topics covered by chapter questions. I think it would be fair to give students a rough idea of some of the topics they are likely to encounter on the tests in advance so that they can focus their study appropriately.

Usually, only one year is dedicated to U.S. history at the high school level. Students who can handle a heavy reading load might double up to complete one of these courses per semester. On the other hand, some parents and teachers might want to expand the second course with coverage of events since 1983, in which case, doubling up might not work.

Even though there are a few quirks, I think students who prefer in-depth history that looks behind the scenes at personalities, causes, and motivations will enjoy these courses.