Like so many Christians, I was introduced to the concept of worldview by Francis Schaeffer's book How Should We Then Live. It was eye-opening and thought provoking as well as the beginning of a long intellectual journey. In many areas, Schaeffer was the beginning of my real education.

Over the years since my first encounter with Schaeffer, I've read and studied worldviews and history, and I concluded that there are areas in Schaeffer's presentation that now appear to me as blind spots rooted in his Reformed theology. For example, Schaeffer implies that St. Thomas Aquinas taught that man was more important than God, seeming to draw this conclusion from Aquinas's rehabilitation of Aristotelian thought (pp. 51-56). Yet, even a brief study of Aquinas is unlikely to leave such an impression. Yet, Schaeffer essentially blames the ill effects of the humanism of the Renaissance on Aquinas while attributing any positive developments to the Reformation. One could just as easily attribute modern-day relavitism to Protestant support for personal interpretation of Scripture rather than dependence upon Church authority. Nothing is quite so simple.

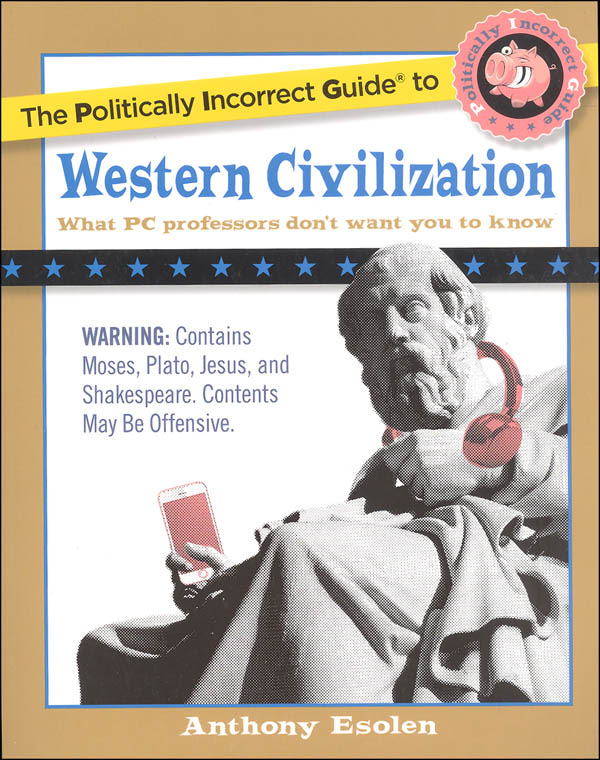

Anthony Esolen helps to broaden and balance the Christian worldview with this brief history that roots Western Civilization in Ancient Greece, Rome, and Israel. Although Esolen's Catholic viewpoint is evident occasionally, he treats Protestantism evenhandedly. While many "Christian" histories treat the period from the Fall of Rome through the Middle Ages as a blighted period of history, Esolen advances the idea that Christianity during this period elevated culture while fostering charity, equality, and tolerance. He also highlights the destruction wrought by Islam as it strove to conquer the world—a topic often sugar-coated in modern histories and given short shrift in light of how huge an impact it had on centuries of history.

He challenges the common notion that the Renaissance and Enlightenment brought reason and wisdom to Western Civilization. Nineteenth century Romanticism's adulation of nature is exposed as a natural precursor to humanism. What began with an implicit atheism became explicit atheism by the twentieth century. Why all of this matters to Western Civilization is then the theme of this book.

Esolen's treatment is heavily religious and philosophical since he believes that Christianity was an essential ingredient in the creation of what has been good in Western Civilization. He also sees the loss of those foundational Christian elements as precursors to the Fall of Western Civilization. Nevertheless, he ends with a hopeful expectation that the ideas of Western Civilization will be revived, if not in the tradtionally western countries, then possibly in Nigeria , Korea, the Phillipines or elsewhere. He concludes, "There is hope for it, if only because it is the sole civilization founded upon hope, because it is founded, finally, upon the word of the One who keeps His promises" (p. 310).

I originally set out to review this book, thinking it might be suitable for homeschooling teens. However, the ideas and language are likely too challenging for most teens. Also, there are occasional sexual references, that although not prurient, assume a adult level of maturity and life experience. In addition, at a total of 340 pages that include forematter, notes, and an index, this is necessarily a very selective treatment of history. Readers with a broad historical knowledge are likely to profit from it much more than those without. Consequently, I would recommend it to adult readers, especially those seeking to broaden or balance their understanding of a Christian worldview.