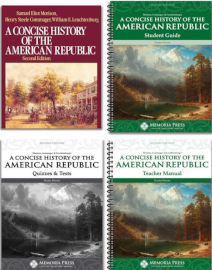

Memoria Press’s one-year high school course for U.S. history uses the 863-page textbook, titled A Concise History of the American Republic, second edition, by Morison, Commager, and Leuchtenburg. About 80 pages at the end are appendices and an index, so it’s not quite as big a book to get through as it sounds. Memoria Press has created a Student Guide, a Teacher Manual, and a Quizzes & Tests book to use with this textbook, and the course carries the same title as the textbook.

The Textbook

This textbook has a long history. The material for this book is drawn from The Growth of the American Republic, a book first published in 1930 and written by Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager. The Growth of the American Republic went through six editions through 1969, with material added each time to cover the intervening years. William E. Leuchtenburg joined the other two authors to work on the sixth edition. Then Leuchtenburg, with some assistance from Morison and Commager, used the material from that sixth edition to create the shortened and revised book, A Concise History of the American Republic, which was first published in 1977. The textbook for this course, the second edition published in 1983, was updated by Leuchtenburg with some editorial input from Commager. It extends through the Reagan era. (Yes, this leaves you on your own to cover the intervening years up to the present.)

Even though it’s supposed to be a concise history, the textbook presents far more detail than students usually learn in high school courses. But that makes it more interesting to read. The authors frequently write about the personal characteristics of important historical figures and the motivations or machinations behind events. For instance, we learn about the character of George Washington as the authors tell us,

He had the power of inspiring trust, but not the gift of popularity; fortitude rather than flexibility; the power to think things through, not quick perception; dignity, but none of that brisk assertiveness which has often given inferior men political influence….And beneath his cool surface there glowed a fire that under provocation would burst forth in immoderate laughter, astounding oaths, or Olympian anger (p. 127).

The overall tone of the textbook is religiously and politically even-handed until, in the last two chapters, some political bias creeps into the coverage of the latter half of the twentieth century. Subtle negativity toward President Eisenhower is followed by laudatory treatment of President Kennedy. A generally positive attitude toward the subsequent Democratic Presidents Johnson and Carter contrasts even more sharply with the critical treatment of Presidents Nixon and Reagan. For instance, Reagan is described as a "right-wing ideologue” (p. 76), and further along, it says, “[I]t was hard to connect so likeable a man to the mean-spirited programs with which he was often associated or so plausible a man to the implausible program he sponsored” (p. 763).

The political bias in the latter part of the book could profitably be used for discussion or further research to provide some balance. Even having students search the text to identify loaded language that might influence readers' opinions would be useful as an exercise in critical thinking.

The overview in the Teacher Manual alerts teachers to problematic cultural content:

While the text is the most thorough, neutral, well-organized treatment of the time period for high school students that we have found, some of the terms used to describe groups of people are now outdated or considered disrespectful…so we have chosen in our guide to use updated language, with the exception of instances occurring in primary sources (p. xi).

Scheduling

This textbook was originally used by Memoria Press over two years, but most high school students need to complete U.S. history in one year. So in 2023, Memoria Press converted it into a one-year course and published new student and teacher books written by Dustin Warren.

The Teacher Manual does not present a specific schedule for covering the textbook’s 36 chapters but gives recommendations for scheduling, including the possibility of covering shorter chapters in less than a week.

The first chapter of the textbook is to be covered briefly or skipped. A note on page 1 in the Teacher Manual says, “Chapter 1 is recommended to be read as review; the content should have been covered in previous American or European history courses.” The first chapter begins with some highly speculative information regarding the first settlers in the Americas, then goes on to discuss the situation in Europe that led to exploration and expansion as well as the native Americans already present before colonization. Chapter 2 begins with the establishment of colonies in what became the United States.

Teacher Manual

After nine pages of introductory information, the Teacher Manual has reduced pages from the student guide with overprinted answers and teaching information surrounding them. The teacher information includes sections titled Introduction, Questions to Mark for the Test, Overview, Summary, and Conclusion.

The Introduction, Summary, and Conclusion highlight key ideas students should consider—what I call the “So what?” of history. For instance, in Chapter 2, part of the Teacher Manual's Introduction section says,

“There are arguments over the story of America. Is America a narrative of freedom? Rebellion? Liberty? Exceptionalism? Religious freedom? Judeo-Christian values? Secularism? Oppression? Is it some of these? All of these? Every American prefers certain narratives over others” (p. 2). The summary and conclusion for this chapter focus on the contrast between John Winthrop and Roger Williams as exemplars of some of these competing values. I very much appreciate this type of information that helps students make connections and understand the value of what they are learning.

Answers for quizzes and tests at the back of the Teacher Manual include both short, predictable answers and lengthy-paragraph answers for the many questions that require a sentence or more. Warren explains, “My answers in the Teacher Manual are full-fledged answers. Students’ answers will probably be nowhere near my length. My intention was to provide as much information as possible for the teacher.” This means that parents whose teens are working independently should have enough information most of the time to evaluate student responses without having to read the textbook themselves. The Overview sections in the Teacher Manual provide an extensive outline for each chapter which should be helpful to parents.

The Questions to Mark for the Test section in the teacher’s information identifies items from the student guide pages that will be on the test. Teachers who need to give students fewer assignments in the Student Guide will want to make sure these items are included.

How the Course Works

The course is intended to be taught. Before students read a chapter, the teacher might present information from the chapter’s introduction in the Teacher Manual to alert them to key ideas, but that information could also be introduced after students have done the reading. Either way, students read the chapter before working in the Student Guide.

The Student Guide has lines for students to write out answers, but students will create a timeline, “character cards,” and cartoons (described below) outside it. Lessons follow a similar pattern for each chapter, although the timeline, character card, and cartoon are not included for every chapter.

The first item in the Student Guide for each chapter is an image of a painting or political cartoon, and these are sometimes the basis for questions posed to students. Following the image is a section titled Introduction that has three items. The first exercise in the Introduction has students write a one or two-sentence summary of the entire chapter. This is followed by one or two quotations that summarize key ideas in the chapter. The third item, labeled “Hooks,” tries to pique student interest by asking them to analyze the image at the beginning of the Student Guide’s chapter, answer a question regarding the quotation, or answer another question related to chapter content such as, “What has been the more crucial invention: automobiles or movies? Explain why?” (Chapter 29: American Society in transition, 1910-1940, p. 168).

Following the introduction section, students write out definitions and descriptions for Key Terms, Key Figures, Key Dates, and Key Structures, although all four “key” types are not included for every lesson.

Next are 6 to 20 comprehension questions, all of which require responses of a sentence or more. A typical question is “How did conflict arise between Texans and Mexico? What happened at the Alamo?” (p. 88). Most lessons follow these questions with one Short Answer Essay Question, such as, “Is John Winthrop or Roger Williams more representative of modern America?” (p. 6). Students are told to write five to eight sentences in response.

Lessons conclude with one or more of the following three assignments: Summative Timeline, Character Card, and Cartoon. The Summative Timeline is an ongoing project students begin for the fourth chapter. Using separate paper, they create a timeline showing key dates. They can illustrate them if they want to, and a sample is shown on page 216 of the Teacher Manual. (Students will be asked to reproduce key events from their Summative Timeline on tests.) Character Card assignments tell students to choose one historical figure from the chapter and on a note card draw a picture or symbol depicting the person or a key event related to the person. On the reverse side of the card, students write key information and two facts not mentioned in the text. (Yes, this requires additional research.) They are to note at least two sources they use. The Cartoon assignment has them create their own cartoon depicting or relating to a historical event.

Parents and teachers might not require students to complete all three types of activities, but the timeline seems most crucial.

Tests

The Quizzes & Tests book has a quiz for every chapter except the first, and a cumulative test after every five chapters. Quizzes have one to three terms to define or explain (or people to identify) plus one to four questions requiring answers at least a sentence long. For example, the Chapter 4 Quiz has three terms for students to explain, followed by two questions that read:

How did the colonies react to the Revenue Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act? How did Great Britain respond to the colonies’ reaction?

Identify the main argument of the Declaration of Independence.

You might have noticed that the questions in the Student Guide and on the quizzes are similar in style, and most will require paragraph-long answers.

Tests cover only the five previous chapters. They begin with a primary source document and questions related to it. These are followed by terms or people to identify, and then by 8 to 15 questions to answer with a sentence or more, questions like those in the Student Guide and on quizzes. One typical question reads, “What were all the factors that drove America to war in 1812? How did it divide the nation?” (p. 34). Next, students recreate their summative timeline. Finally, they write an essay in response to questions such as, “Outline and summarize the long-term causes of the early and mid-1800s that led up to the Civil War” (p. 52).

The tests seem quite daunting since the short essay questions will rarely be answerable in less than a paragraph. Warren leaves it up to the teacher to decide whether to give students an idea of topics they are likely to encounter on the tests in advance so that they can study appropriately, but I highly recommend doing so.

Summary

A Concise History of the American Republic is an excellent text, but it is lengthy. In addition, the course requires a significant amount of writing between the Student Guide, weekly quizzes, and tests. Because of the amount of reading and writing, the course will be best for students who have developed excellent skills in both areas. Nevertheless, it is an outstanding course for covering U.S. history that should appeal to students who prefer in-depth history that looks behind the scenes at personalities, causes, and motivations.